The Iron Triangle Claimed the Last 18th FBW Mustang Pilot

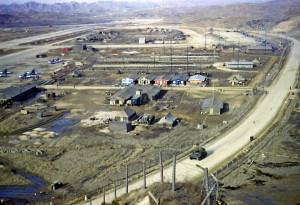

It was nearly dark at 1915 hours on 25 July 1952, when Captain Elliott Dean Ayer, Flight Leader of Filter How Flight was “wheels up” from K-46, Hoengsong, SK, on a twilight reconnaissance of a North Korean MSR.

It was rapidly getting dark, making it harder for ground observers to make out the “655” side number or the “Lovely Lady” on the left cowling or “Lady Louise” on the right cowling. His four-ship flight included 1st Lt. William McShane flying Number Two, 1st Lt. C. J. Gossett was Number Three, and 1st Lt. Rexford R. Baldwin was Number Four. Ayer was one of the Korean War’s most experienced pilots and leaders, having served with distinction as a soldier, NCO and combat pilot during WWII. He was highly experienced in the F-51 Mustang, having earned several decorations for his bravery during heavy air combat in the Italian theater in WWII. Following his appointment as How Flight Leader of the 67th Fighter-Bomber Squadron on 1 June just a few weeks before, he had been selected by the 18th FB Wing to fly its historic 45,000th combat mission, a great personal honor.

Further, he had been recommended for another Distinguished Flying Cross for his leadership in directing Mission 1890 on June 25th, a harrowing helicopter extrication of a Navy Corsair pilot from off the side of a mountain west of Wonsan under heavy fire. The mission involved six Mustangs and one H-5 Dragonfly helicopter. Tragically, although the rescue mission was initially successful, the waiting Chinese used Ens. Ron Eaton as bait, and shot the helicopter down five miles from the site. Minutes later, Ayer’s wingman, 1st Lt. Archie Connors, was also shot down while making a “low, fast pass” over the helicopter crash site to ascertain the fate of its crew and passenger. Mission 1890 became the most deadly helicopter rescue of the Korean War. Tonight was to be just another twilight MSR interdiction. But for Captain Ayer, it was the last mission, the one from which he never returned. He became the last 18th FB Wing Mustang pilot killed in combat before it transitioned into the F-86 Sabre-jet in February 1953. © Copyright 2015 BelleAire Press, LLC Next: Pearl Harbor Veteran